The Atacama Cosmology Telescope in the high Chilean desert mountains has just given up its final batch of data

The Atacama Cosmology Telescope in the high Chilean desert mountains has just given up its final batch of data

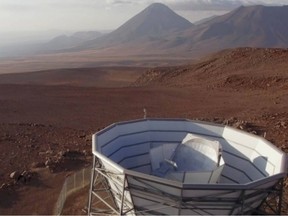

The Canadian-built Atacama Cosmology Telescope in the high Chilean desert mountains, which has just given up its final batch of data from looking into the heavens for the lingering glow of the Big Bang, was built in 2006 near Vancouver by a company that also makes rollercoasters.

That is no mere coincidence. Amusement park rides present similar engineering problems as big telescopes: extraordinarily precise motors that move smoothly through their motions, rigorous data collection, and lots of regulatory and managerial hoops to jump through.

So when he travelled to Port Coquitlam to help assemble this six-metre telescope for a 2006 trial run before the container ship journey to South America, Adam Hincks, a University of Toronto cosmologist who is also a Jesuit priest, had a peek into the workshop and spied a theme park ride under construction. He doesn’t remember which one, but a look through Dynamic Structures’ projects (formerly AMEC) suggests it might have been something for Disney or Universal Studios.

Worlds collide like that in frontier cosmology. ACT illustrates this better than most science projects. It brought an international team together up where the air is thin on the Andean cordillera, near the Bolivian border, in a landscape of salt lakes, flamingoes, geysers, and abandoned sulphur mines, sparsely populated by curious creatures like the vicuna, a type of wild camel. It’s the perfect place to look so far up you look back in time.

On Tuesday, a set of papers based on the sixth and final data release from ACT are to be presented at the American Physical Society meeting in Anaheim, Calif. They represent the final reports from a science experiment that aimed to look farther than any telescope had before, indeed as far as physically possible.

When it took first light in 2007, ACT was observing electromagnetic waves that had literally been travelling through space since the origin of the universe, 14 billion years ago, give or take. The trajectory of each photon ACT has detected over the last two decades extends back from this telescope on the slopes of the Cerro Toco volcano all the way to the newborn universe after the Big Bang, more specifically to the first high frequency microwaves that were emitted when the universe, at about 380,000 years old, cooled from a hot plasma into gas, on its way to becoming the cold vastness we see today, punctuated here and there with stars, black holes, dust clouds, dark matter, and a few comparatively tiny planets.

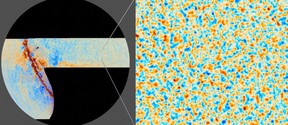

ACT’s mission was to map this Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), this glow that represents the first cooling of that primordial plasma into hot gas, when the first light that ever shined radiated through this new universe from matter that would later collapse under gravity into the first stars.

At that time, 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the matter in the universe went through this phase shift “pretty quickly,” from electrically charged plasma to electrically neutral gas, Hincks said in an interview. “It’s at that moment, during that transition, that light gets liberated…. Now you can see vast distances.”

ACT succeeded in its mission to map this radiation, both its temperature and now also its polarization. Hincks calls the project a “resounding success” with more than 100 published papers.

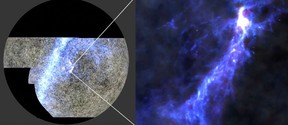

It also allowed the collaboration to make a proxy map of dark matter across a quarter of the sky, a tricky project because dark matter is in principle invisible. It can be detected, however, by studying how the CMB has been distorted in its journey across the universe by the gravity that dark matter exerts.

The experiment also offered one side of what Hincks calls a fundamental “tension” in observational cosmology. It’s about how fast the universe is expanding, known as the Hubble constant. One way to measure this is by looking at supernovae, star explosions, which are well understood in terms of how their light should appear, so the measure of how much that light is shifted to the red end of the spectrum is a direct measurement of how fast a supernova is receding from Earth.

Distant galaxies are not just far away. They are receding from ours and from each other, the farther away the faster, like raisins in a rising cake. Their light waves that reach Earth are therefore shifted to red, sort of stretched into longer wavelengths, on the same principle as the Doppler effect in sound waves, which makes a siren sound high pitched as it approaches and lower after after it passes.

Another way to measure the universe’s expansion speed is by looking at ripples in the CMB. Trouble is you get different answers. Not a lot, but given how precise the measurements are, the two observed speeds are “very inconsistent,” Hincks said.

“So there’s still this tension,” Hincks said. “It could be there’s a source of error that is not understood in either or both techniques. Or it could be that there is something fundamental about the universe that we don’t understand…. We think we know how universe expands and evolves, but maybe we’re a little bit wrong.”

We think we know how universe expands and evolves, but maybe we’re a little bit wrong

This telescope collaboration “changed the game for small scale CMB science,” said Renée Hložek, a theoretical cosmologist and associate professor at the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, who joined ACT in 2008, and has worked on its projects to clarify and confirm existing theories, in what she called friendly competition with the South Pole Telescope, in a similarly high, dry, cold place.

They did all this, Hložek said, against the steep challenge of being on the ground.

The best way to observe the CMB is in space. On Earth, you have no choice but to look through the atmosphere, which is full of water vapour. This absorbs the very light they are looking for, and it also emits microwave radiation of its own that blurs and distorts the image. Some of that interference can be corrected with sophisticated analysis. Some cannot.

There are other problems. The best time to look is at night. You can detect microwaves in the daytime, but the heat of the sun tends to distort the mirrors, so the data is useable but not as good as at night.

But a ground based telescope also has advantages over space-based competitors, such as the European Space Agency’s Planck and NASA’s WMAP.

The main advantage is the ability to constantly upgrade the kit, Hložek said. For example, the detector and camera were changed three times throughout ACT’s operational life, before it was decommissioned in 2022.

To see this Cosmic Microwave Background radiation, the telescope’s detectors must be cooled with liquid helium and vacuum techniques to hundreds of millikelvins, almost impossibly cold, because the radiation they are measuring is so cold to begin with. Some of the key engineering advances have been in refrigeration, Hložek said.

And the detectors themselves are revolutionary, Hložek said. They are called transition edge sensors, quantum devices that are kept close to superconducting temperatures so that when a photon from the CMB hits a detector, it causes a big change in its superconductivity. That gets recorded and stored to build up a map of that radiation across much of the sky, except for example in the part of the sky that’s obscured by the bright Milky Way, or the part on the other side of Earth that a ground-based telescope cannot see.

In the early days, data would be collected onsite in hard drives, stowed in carry-on luggage, and brought by staff directly to specially designed supercomputers in Toronto for analysis. Lately, their internet connectivity got better so the data travels separately.

“One of the things we are afforded by such exquisite data is the ability to stress-test the model,” Hložek said.

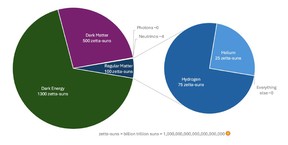

She means the theoretical model of how the universe expanded out from a single point of infinite density and temperature, and continues to expand today. This model is called Lambda-CDM, for the Greek letter lambda that represents a cosmological constant to account for the universe’s expansion driven by dark energy, plus the abbreviation CDM for “cold dark matter.”

It’s not the only model, but it is holding up well under ACT’s observations.

A press release says the “Atacama Cosmology Telescope collaboration has put the standard model of cosmology through a rigorous new set of tests and show it to be remarkably robust. The new images of the early universe, which show both the intensity and polarization of the earliest light with unprecedented clarity, reveal the formation of ancient, consolidating clouds of hydrogen and helium that later developed into the first galaxies and stars.”

One of the new papers is on the CMB maps and how they were made. Another is on how observations relate to Lambda-CDM. Hložek contributed to a third paper on the theme “beyond the Lambda-CDM model,” and said after testing a range of other possible models, the “scary exciting thing we find” is that Lambda-CDM is actually a “good fit.”

“The data is consistent with our simple picture,” she said. The “puzzle” is why it seems so simple even as the data get ever more precise.

“It’s beautiful that the universe has a consistent picture,” she said. But it’s also challenging.

Hincks said he is likewise struck by this powerful evidence that the universe in its early stages was “elegantly simple.”

“And then to think out of that elegant simplicity 400,000 years after the Big Bang that we have this beautiful richness, in today’s universe, that this richness emerged out of this very simple starting point that we can describe remarkably well,” he said. He said it brought to mind Einstein’s saying that the fact the universe is comprehensible at all is a miracle.

Hložek sees the final data release from ACT as not quite an ending but the passing of a baton to other experiments, such as the Simons Observatory that is in place nearby and partly functioning with multiple telescopes, so more like the “dusk of one and the dawn of another.”