The diss track reached its peak of cultural prominence at the Super Bowl, when Kendrick Lamar performed Not Like Us, his hit diss track against Drake

The diss track reached its peak of cultural prominence at the Super Bowl, when Kendrick Lamar performed Not Like Us, his hit diss track against Drake

Reviews and recommendations are unbiased and products are independently selected. Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through links on this page.

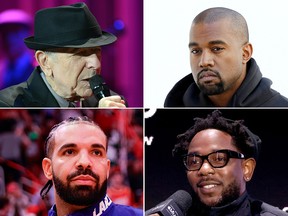

It has been 10 years since the late great Canadian poet singer Leonard Cohen wrote the poem “Kanye West Is Not Picasso,” and though he did not live to record it in song, it reads like a diss track.

“Kanye West is not Picasso / I am Picasso / Kanye West is not Edison / I am Edison / I am Tesla / Jay-Z is not the Dylan of anything / I am the Dylan of anything / I am the Kanye West of Kanye West,” reads the poem as it builds toward its most cutting line: “I am the Kanye West Kanye West thinks he is.”

Published in Cohen’s posthumous collection The Flame: Poems and Selections from Notebooks, and dated at the bottom March 15, 2015, the poem has all the familiar stylistic elements of this musical insult form: an aggressively confident tone; a specific famous target for the overt disrespect; clever insults that are poetically indirect and almost funny; a target no less famous than the author; and the hint of a love/hate relationship between them. All it lacks is a tune.

And it has aged well, acquiring new poetic meaning and an eery sense of prescience as West continues his slide into moral depravity even to the point of Nazism. Truly, he is not Picasso. But 10 years ago, when he was regarded as an artistic genius, it took our man Leonard to say so in verse.

Today, the diss track has reached its greatest ever cultural prominence, peaking a few weeks ago at the Super Bowl, when rapper Kendrick Lamar performed Not Like Us, his Grammy winning hit diss track against Drake with its allegedly defamatory insinuations of pedophilia, which was the ultimate victory for Lamar in a long running exchange of diss tracks. Once the other guy sues, as Drake has, a disser has already won.

With expert guidance in ethnomusicology from Jeremy Wallach, an anthropologist at Bowling Green State University in Ohio who studies the popular culture of music, the National Post’s Joseph Brean compiled 10 rules about diss tracks for the 10 years since Leonard Cohen vs. Kanye West.

1. Diss tracks are usually traced culturally to The Dozens, a game of wit in African American culture between two contestants, usually young men, who take turns insulting each other with increasing severity, winning when the target responds with anything but a better joke delivered gracefully, and especially if they respond with anger. Often using the “Your mother is so…” construction, The Dozens was precursor to the more elaborate battle rap style. Insult songs also draw on wider and older historical traditions. “Music is an ideal form for exploring the airing of opinions and sharing scandalous rumours, which you don’t necessarily get to say in the press because you might get sued for slander, even if you say them in disreputable places like tabloids,” Wallach said. Musical lyrics can be poetic, indirect, and they are often less heavily censored or regulated than printed words. “As a scholar I look at these cases, going back to Yankee Doodle (the “macaroni” lyric was a diss meaning a foppish dandy) by loyalists against patriots in the Revolutionary War.”

2. Diss tracks rely on a sense of tribalism. “What most of these have in common is that there’s more on the line than just the egos of the combattants. I think that’s really crucial, that they are representing constituencies. They are speaking for a community, an identity, that is larger than themselves. That is why the feuds are compelling to audiences. That’s why the punches land satisfactorily,” Wallach said. Cohen’s poem, for example, is not just a Canadian dissing an American, or an old man dissing a younger man. Now it sounds like he’s “striking a blow for Jews against a Black Nazi,” Wallach said. “I think the real epic diss tracks are about people really representing more than themselves.”

I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes / You’d know what a drag it is to see you

3. Diss tracks rose to prominence in America in the 1980s with the hip-hop rivalries known as the Roxanne Wars, then became established as a major musical genre that drove record sales in the East Coast and West Coast rapper feuds of the 1990s. The best known diss tracks among the former members of N.W.A. and between Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls reinforced the standard practice that diss tracks should be between more or less equals. Aiming at someone bigger was aspirational and risked being ignored in return. Aiming at someone smaller was cheap.

4. The diss in question should be as funny and clever as it is vicious. Lynyrd Skynrd took a shot at Neil Young for his anti-racist songs Southern Man and Alabama, with the lyric in Sweet Home Alabama that, “Well, I hope Neil Young will remember / A Southern man don’t need him around anyhow.” It was good southern rock, but it wasn’t much of a diss. “In hip-hop, you get points for cleverness,” Wallach said. Eminem’s song Without Me, for example, took down Moby with the line “You don’t know me, you’re too old, let go, it’s over, nobody listens to techno.” Eminem’s more recent diss of Machine Gun Kelly on Killshot is even funnier: “How you gonna name yourself after a damn gun and have a man bun?” But the insulting artist gets most points for cleverly veiling his meaning, and few diss tracks have hit this sly note better than the best known line in Not Like Us, which Lamar’s Super Bowl audience sang along to, that Drake is “tryna strike a chord and it’s probably A minor.”

5. The target can be anonymous but should be specific and real. Sexy Sadie by the Beatles, for instance, is about John Lennon’s lowered opinion of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi at the end of their stay with him in India: “Sexy Sadie, you’ll get yours yet / however big you think you are.” Lennon took another stab at a diss track later in anger at Paul McCartney in How Do You Sleep, with the savage but almost self-defeating diss lyric: “The only thing you done was Yesterday.” Or even more creepily: “Those freaks was right when they said you was dead.” Actually naming the target is not necessary. A little mystery helps. Sometimes the target remains widely unknown, at least for certain, but wondered over, as in the enduring mystery of whether Carly Simon’s You’re So Vain (“you probably think this song is about you”) refers to Warren Beatty, Kris Kristofferson, Mick Jagger or James Taylor. But it’s obviously someone like that. On the other hand, CeeLo Green’s Motown-styled hit “F–k You,” in which he sees another man “driving round town with the girl I love and I’m like, ‘F–k You’” has some elements of a diss track, but is not really one. His target is not presented as a concealed celebrity, just some rich guy who stole his girl, and in fact Green has said the song is actually about his bitterness toward the recording industry. You can’t really diss a metaphor. On Positively 4th Street, on the other hand, Bob Dylan is clear he and the target ran in the same crowd, before the dissing began, putting that song more credibly in the genre: “Yes, I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes / You’d know what a drag it is to see you.”

6. Releasing a diss track is playing with fire. There are perils, even to the disser. Clever cruelty comes at a personal cost. Rollie Pemberton, who raps as Cadence Weapon, wrote in the online literary magazine Hazlitt about the Lamar/Drake feud that “it feels like an example of what can happen when men have unresolved trauma: they inevitably take it out on others. Kendrick may have won the battle in the court of public opinion, but what has he lost by stooping so low? His album about the importance of therapy and dealing with trauma was initially ignored by the masses but now he’s been rewarded with a number one hit in which he gives into his most base impulses.” Wallach similarly spoke of the potentially negative effect on audiences. The Lamar/Drake feud came up in a recent graduate seminar he runs at Bowling Green State University, in which one student, a woman of mixed race, expressed her own discomfort at this symbolic expulsion of the lighter skinned Drake from this musical community on partly racial grounds.

7. There are diverse precedents and analogs in other genres, even classical music. Written for fun to a friend, the lyrics to Mozart’s comic canon “O du eselhafter Peierl,” call its target “asinine,” “idle as a nag… I’ll see you hanged yet,” before inviting him to “kiss my ass.” There are also hints of the tradition in poetry, as when the African American poet Langston Hughes riffed on Walt Whitman’s poem “I Hear America Singing,” which presents an idealized vision of American enterprise as a kind of singing by masons, carpenters, boatmen and shoemakers. “I, too, sing America,” Hughes wrote. “I am the darker brother. / They send me to eat in the kitchen / When company comes, / But I laugh, / And eat well, / And grow strong. / Tomorrow, / I’ll be at the table / When company comes. / Nobody’ll dare / Say to me, / “Eat in the kitchen,” / Then. / Besides, / They’ll see how beautiful I am / And be ashamed– / I, too, am America.”

More recently, Grimes, the Canadian singer and ex-girlfriend and co-parent with Elon Musk, recorded a diss track about him in her avant-garde electronica style, in which she sings: “I’m in love with the greatest gamer, but he’ll always love the game more than he loves me.” It wasn’t a hit, though, partly because it lacks the bitter note of revenge in other post-romantic diss tracks like Justin Timberlake’s Cry Me A River about Britney Spears, or You Oughta Know by Alanis Morissette about Dave Coulier.

Those freaks was right when they said you was dead

8. Diss tracks are not a heavy metal thing. Nor punk. “It just wouldn’t sound right,” Wallach said. “Metal tends to be about the individual versus society. It tends to be impersonal in its portrayal of obstacles and malevolent forces. You’re generally struggling against evil, social injustice, addiction, generally impersonal malignant forces, monstrous forces, but not people. You generally don’t have personal vendettas in metal, you don’t have named individuals. It would be very unidiomatic for the genre. The same also would go for punk.”

9. The tribalism of diss tracks can be put to use for patriotic purposes. For example Neil Young recently announced a free concert in Ukraine to support the embattled country, and ended the announcement: “Keep on Rockin’ in the FREE WORLD,” which was a song that originally criticized George Bush the elder and his Republican administration in the late 1980s. Chantal Kreviazuk arguably even turned O Canada into a diss track by singing alternative lyrics, “… that only us command …” at the recent 4 Nations Face-Off hockey final. Cohen’s poem about West also has a martial feel toward the end, with its final line that hints at greater conflict: “I don’t get around much anymore / I never have / I only come alive after a war / And we have not had it yet.”

10. A diss can seem like a confession of affection as much as an insult. In music as in life, hate and love are not exactly opposites, and often coincide as elements of the same relationship. So trading diss tracks often come across as a confession of closeness, of mutual inspiration. Kendrick Lamar and Drake were collaborators before they were enemies. Likewise, the Canadian music critic Carl Wilson wrote that Cohen’s poem about West is “not an insult to Kanye West. It’s a tribute.” His theory was that Cohen “was amused by Ye’s over-the-top braggadocio and impressed by his rhetorical style, wanting to get in on the fun.” Maybe. Whatever he felt, it was not mutual. Kanye West never wrote a song about Leonard Cohen. But Joni Mitchell might have. It was a love song called A Case of You (which also might be about Graham Nash). It includes the clever title pun comparing the subject to both an illness and a case of wine, and also the poignant lyric that “part of you flows out me in these lines from time to time.” If the song really was about Cohen, it’s fun to imagine a poet of his caliber hearing Canada’s queen of songwriting criticize his cheesy simile like this, in her plaintive opening line: “Just before our love got lost you said / “I am as constant as a northern star” / And I said, “Constantly in the darkness / Where’s that at? / If you want me I’ll be in the bar.”

Ouch.